The news from Brunei Darussalam is grim. The small Southeast Asian, oil and gas-rich country, has announced plans to implement a new legal code that, among other things, calls for amputation for those convicted of theft and for death by stoning for homosexual acts. After an international outcry, the Government has delayed the imposition of the death penalty, but it maintains the laws as the presumptive legal framework.

These laws violate basic human rights, but from experience, I realize that this argument doesn’t seem to be convincing to everyone. As a development economist, I then thought, what are the economic costs of this? Particularly, I wondered if there was likely to be an impact on the broader economy of restrictions on the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community. As I discuss below, the answer is, ‘yes, over the long-run, a lack of freedom for the LGBT community is associated with a less entrepreneurial economy—a less dynamic economy.’

This is important to Brunei. Strictly in economic terms, the country has done very well for its people. Oil and gas exports have provided a high standard of living. In 2017, GDP per capita for Brunei was estimated to be $28,787, much higher than regional neighbors. The government subsidizes many aspects of everyday life, including housing, education, health services, and household utilities.

These riches depend on oil and gas exports and therein lies a problem. Hydrocarbon resources do not last forever. While technological change in the industry has expanded exploitable resources, this is not something that can be relied upon to underwrite a high standard of living indefinitely.

The government of Brunei has long acknowledged this. Since the 1960s, the development plans for the country have included calls to diversify and to encourage the growth of a vibrant private sector, partly by encouraging entrepreneurship, to create an environment in which people start businesses, investing in their own economy. The government’s development plan, Brunei Vision 2035, commits the country to “a local business development strategy that will enhance opportunities for local small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs)...”

There are many strategies to encourage entrepreneurship; every country walks a different development path. But broadly, entrepreneurs need to feel comfortable in accepting the risks that are attendant to growing a business. I suggest that the failure to recognize the personal freedoms of the LGBT community will discourage entrepreneurial activity. Three aspects are important:

- The impact of discrimination against the LGBT community on entrepreneurial dynamism is not because LGBT individuals are all entrepreneurs, although many are. It is because treatment of LGBT people sends a powerful signal as to how the government may treat others. I am saying here when one group does not feel safe, other people worry about their safety, depressing the willingness to take the risks of building businesses. The experience in Europe in the last century is a powerful example of this. (The words of German Pastor Martin Niemöller, himself a World War II concentration camp survivor, speak powerfully to this point.)

- Discrimination against, oppression of, the LGBT community likely encourages these people to relocate to more accepting locales. This is the experience within the United States. Waverly Deutsch (2016) concludes, “There is a clear migration away from intolerant locales toward states and cities with prodiversity policies.” This has the impact of depriving the less tolerant place of human resources.

- The world is becoming more open in the sense that what happens to people in one place is less likely to remain hidden than it was in the day before the Internet. A generation ago, what happened in Brunei stayed in Brunei. Today, with email, Instagram, and Facebook, not to mention world news organizations, less can be concealed. Thus discrimination, oppression of the LGBT community is something that would be known. In some instances, this can have clear costs. For instance, recently the actor/activist George Clooney was able to organize a well-publicized boycott of a hotel chain owned by the Sultan of Brunei in protest of the new legal code.

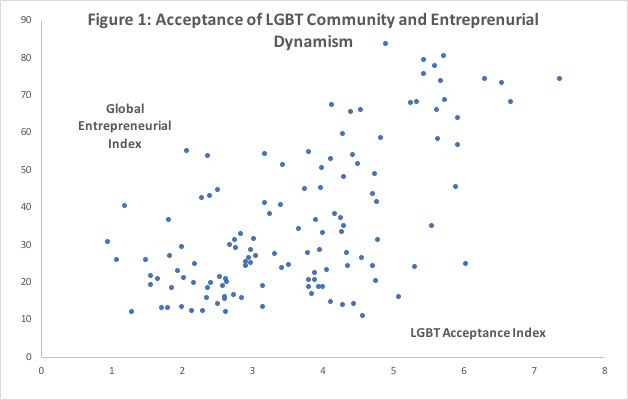

Testing this hypothesis—that discrimination against the LGBT community discourages entrepreneurial dynamism—is not easy. There is no one model to explain entrepreneurial activity. But we can approach the subject using some work by Andrew R. Flores and Andrew Park. They fashion an LGBT Global Acceptance Index (GAI) using a wide series of indicators measuring “prevailing opinion about laws and policies relevant to protecting LGBT people from violence and discrimination, and promoting their equality and well-being.”

The LGBT GAI represents considerable effort, aggregating surveys providing for more than 1.4 million responses to questions, focused on attitudes towards the LGBT community, covering 141 nations. The index can vary between zero and ten, from least to more accepting of the LGBT community. Flores and Park provide indices for five-year averages for 138 countries. I use below, for each country, the average LGBT GAI for 2009-2013. (Unfortunately for the purpose here, Brunei is not included in the database.)

I compare the LGBT GAI to an index that provides a measure of the entrepreneurial dynamism of the country, the Global Entrepreneurship Index (GEI) produced by the Global Entrepreneurship and Development Institute. The GEI "is a composite indicator of the health of the entrepreneurship ecosystem in a given country.” The GEI combines 14 sub-indices, ranging widely through such topics as the ability of individuals to network with each other, market openness (competition), and the availability of capital. The index value for Brunei ranks 53 out of 137 economies included, showing considerable room to improve relative to what other countries have achieved.

The two indices were paired for 125 economies that were included in both databases. The scatterplot is below. The correlation between the two variables is 62%. Fairly clearly, those countries with dynamic entrepreneurial sectors are those that tend not to discriminate against the LGBT community. Conversely, those countries that do not accept the LGBT community typically show little entrepreneurial dynamism.

While the relationship between the two variables is apparent, it is not true that in every case, at every moment, discrimination against the LGBT community is clearly associated with a lack of dynamism in entrepreneurship. Some countries appear to be able to flout my warning. This is not surprising, every country follows its own path and outcomes on any given metric may not show any particular relationship. Analogously, we all have the experience of knowing some people who smoke, yet seem perfectly healthy. But over the long run, smoking will likely bring you down. Similarly, a dynamic entrepreneurial economy will require a society tolerant of and respectful of the LGBT community.

Somewhat more than a decade ago, I worked in Brunei, helping the government craft capital market rules that would both honor Islamic Sharia Law and be relevant to today’s needs. I understand the desire to honor tradition. The trick is to honor tradition in a way that is relevant to the needs of today. In the case of the LGBT community, the only real way forward is to end discrimination.