Loss of the Journal of Asian Economics to a takeover by Elsevier and less than encouraging responses from other publishers to inquiries about starting a new journal prompt these remarks. Why did the model of an academic society choosing editors, setting a vision, and developing content stop working for Elsevier? And is there a future for such a model?

The Journal of Asian Economics was founded in 1990 by the American Committee on Asian Economic Studies. During its 30 year run under ACAES auspices, the Journal was helmed by three Editors-in-Chief: founder Manoranjan Dutta (1990-2007); Michael Plummer (2007-2015); and myself (2015 to the June 2020 issue). The Editor-in-Chief served concurrently as President of ACAES with endorsement by the organization's voting members.

Initially, the publisher and owner of the Journal was JAI Press. Elsevier acquired JAI Press in 1997, and began publishing the Journal under its own imprint in 2000. Throughout, the Journal carried the branding "Published for the American Committee on Asian Economic Studies". And throughout, ACAES appointed the Journal's Editor-in-Chief, who in turn enlisted other members of the editorial board, with the publisher's concurrence.

Breaking with 30 years of precedent, Elsevier on March 18 offered me a one-year terminal contract for 2020, signifying that thereafter the publisher would be taking charge of editor selection. This would effectively sever the tie between ACAES and the Journal. Hoping their voices would matter, the Journal's academic stakeholders launched a letter writing campaign that generated 43 statements, posted here. But Elsevier was unmoved, and I resigned rather than acquiesce to such usurping of power.

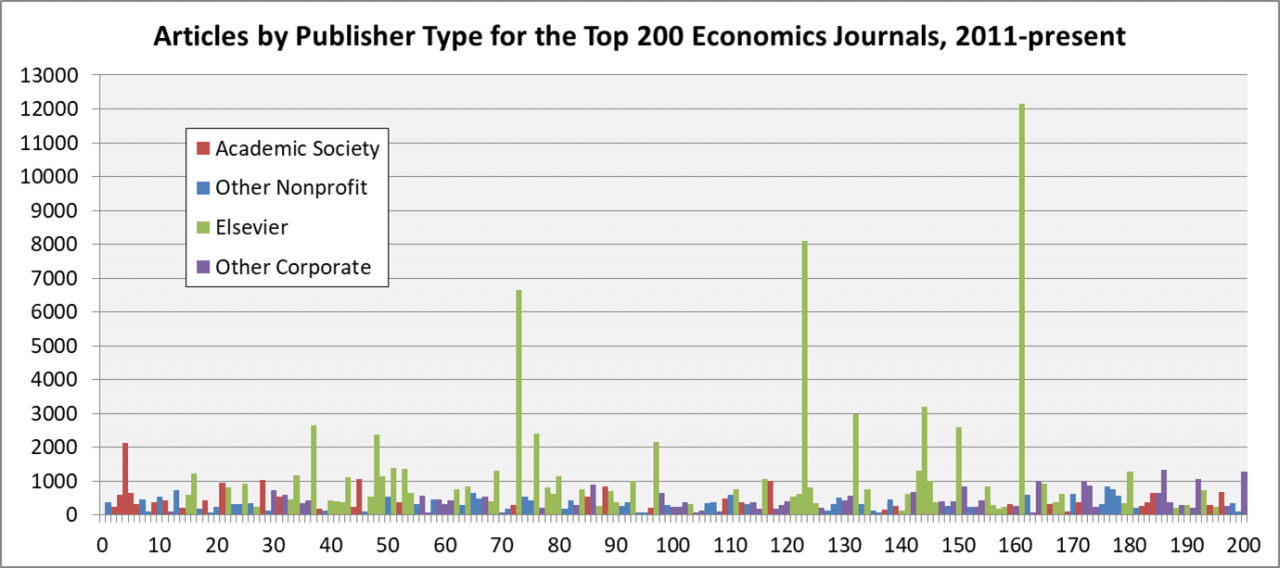

The reason for Elsevier's termination of my editorship and the relationship with ACAES was not any problem with the quality of our publications. Indeed, the 43 stakeholder statements extol our performance on that front. Rather, the publishing agent pointed to concerns with quantity and speed. The Elsevier business model has been all about gaining a position of market dominance. The numbers tell of great success in this regard. The table below presents statistics on Elsevier's standing within the top 200 economics journals based on the RePEc 10-year simple impact factor for the period since 2011. Elsevier's share of all articles published was an awesome 58.6%. Its share of journals was a more modest 32.0 percent. These figures imply a far greater number of articles per journal for Elesvier than for other publishers. The average for Elsevier was 1287, or about 140 articles per year, in contrast to around 40-50 articles per year for other publisher types. Medians are lower with Elsevier at 750, or around 80 articles per year versus about 35-40 for other publisher types.

Summary Statistics by Publisher Type for the Top 200 Economics Journals, 2011-Present

| Academic Society | Other Nonprofit |

Elsevier | Other Corporate |

|

| # of journals | 34 | 52 | 64 | 50 |

| % of journals | 17.0 | 26.0 | 32.0 | 25.0 |

| # of articles | 17,394 | 18,249 | 82,375 | 22,642 |

| % of articles | 12.4 | 13.0 | 58.6 | 16.1 |

| mean articles/journal | 512 | 351 | 1287 | 453 |

| median articles/journal | 382 | 333 | 750 | 379 |

Data source: RePEc 10-year simple impact ranking (9 June 2020), spreadsheet here.

The number of articles published for the full range of 200 journals is shown in the figure below. Elsevier's dominance of the high output journals comes through clearly. Of 11 journals that have published more than 2000 articles since 2011, all but one are Elsevier journals, the lone exception being the American Economic Review ranked by RePEc at #4. Of 31 journals that have published more than 1000 articles since 2011, 23 are Elsevier journals with 8 being non-Elsevier journals.

The Journal of Asian Economics ranks at #167 in the figure and shows 366 articles published for the period. The Journal's output saw a decline through the first half of the decade and stabilized under my editorship. We published 33 articles in 2019, up from 30 in 2018 which was when pressure on us to increase output began. These numbers are close to the medians for non-Elsevier journal categories.

I explained to Elsevier representatives that we followed a model in keeping with the ACAES sense of mission. We looked for papers that were well motivated by the particularities of Asian economies and yielded meaningful insights for the Asian context. If papers that fit this bill needed work on methodology and presentation, we helped with that. By the same token, we rejected papers that presented mechanical applications of technique to data where the data just happened to be from Asian countries, no matter whether the methodology was competently executed and the writing was fine. Our emphasis was on promoting thoughtful inquiry and lending support in the development of scholarship. Authors who benefited from this treatment were very grateful (see, for example, letters to Elsevier from Iqbal and Toh). Explaining this to Elsevier representatives, I tried to convey that the model does not scale up and it does not speed up. Yet it did yield high quality publications in numbers on par with other reputable journals. More importantly for a journal affiliated with an academic society, our work contributed to the advance of the economics profession.

All this was of no import to Elsevier. Even the Journal's strong improvement in citation metrics did not matter. Elsevier publishes journals across the range of journal rankings. That some of its journals move up and correspondingly others move down does not alter the totality of the Elsevier presence in the marketplace. And it is this totality that is key when it comes to negotiating subscription fees with libraries. Libraries generally must buy the package, and the bigger the package the more market power Elsevier wields.

With the Journal of Asian Economics in particular, I suspect Elsevier has designs on broadening its power in a global market. In the spring of 2019, the Journal was assigned to Elsevier's Beijing subsidiary. Following my ouster, the position of Editor-in-Chief was conferred on a Chinese national. In its post-ACAES form, the Journal is taking a much broader purview, no longer actually limited to Asia but open to work of all varieties with Asia figuring only "particularly". By developing a broad based journal under Chinese control, Elsevier's strategy is seeminly to ramp up publication by Chinese authors and to thereby increase its leverage in marketing the journal in China. And the land of billion customers has a lot of libraries!

While the sinification of the Journal of Asian Economics may represent good business strategy for Elsevier, I am concerned about the implications for the Journal's integrity of having a Chinese publisher and a Chinese editor in charge. China practices heavy handed academic censorship and the blacklisting of foreign scholars from which the Journal will not be immune. The Chinese publishing agent I dealt with once interrupted me in mid-sentence when I referred to "Taiwan" to correct me with "Taiwan, China". Under my editorship, we routinely received submissions from Chinese authors with propagandistic overtones on the Chinese development model or the Belt and Road Initiative or what-have-you with respect to China. Chinese principals will have a different sensibility on such matters than Americans. For a journal founded by an American academic society that held research objectivity and pan-Asia balance in the highest regard, Chinese appropriation represents an ominous twist.

___________________________

Further posts in the series:

The State of Journal Publishing: Barriers to Entry

The State of Journal Publishing: Elsevier on Gender

Discussion continues in the ACAES Newsletter of Sept 2020 with attention to how academics are taking control.