In recent years, emerging market countries—in particular, those in Asia—have been among the global economy’s star performers. Even during bad times, such as during the Global Financial Crisis, Asian EMs have seen their economies hold up better than most others.

For much of the COVID crisis, that story held true. Many Asian economies, such as Vietnam, Singapore and Taiwan, seemed to have COVID under control, while Asian EMs appeared to have significant monetary and fiscal policy room to help address any economic impact of the crisis. In April 2021, the IMF’s projections for growth in the region were extremely bullish, with a recovery to 8.5 percent growth in emerging Asia this year and 6.0 percent in 2022. Two months later, expected growth had been downgraded, to a still-healthy 6.3 percent and 5.2 percent over the same two years (see Table). The ADB was even more optimistic in its July 2021 projections, pointing to growth of 7.2 percent and 5.4 percent this year and next.

For much of the COVID crisis, that story held true. Many Asian economies, such as Vietnam, Singapore and Taiwan, seemed to have COVID under control, while Asian EMs appeared to have significant monetary and fiscal policy room to help address any economic impact of the crisis. In April 2021, the IMF’s projections for growth in the region were extremely bullish, with a recovery to 8.5 percent growth in emerging Asia this year and 6.0 percent in 2022. Two months later, expected growth had been downgraded, to a still-healthy 6.3 percent and 5.2 percent over the same two years (see Table). The ADB was even more optimistic in its July 2021 projections, pointing to growth of 7.2 percent and 5.4 percent this year and next.

It now appears unlikely that emerging Asia will come close to these projected growth levels. There are several reasons for this:

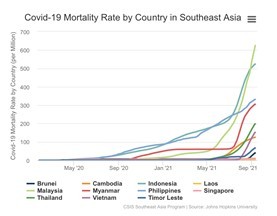

- The impact of COVID on regional economies has increased sharply in recent months. This is due to the spread of the Delta variant of the virus as well as slow rollouts of vaccinations in many countries in the region. In addition to the terrible toll on lives (see Figure), the need to shut downs parts of the economy appears to have slowed growth considerably. In countries that rely heavily on tourism—such as Thailand—the impact may be particularly significant.

Inflation has risen in much of the global economy, and emerging Asia is no exception. In part, this reflects possibly transitory effects of supply chain disruptions and sharply rising shipping costs, which have also impacted exports from the region. But central banks will likely feel the need to address concerns about rising prices, perhaps following recent rate hikes in Korea, Turkey, and Russia. At a minimum, the likelihood that central banks will offer significant policy support in the current environment seems to have declined considerably.

Inflation has risen in much of the global economy, and emerging Asia is no exception. In part, this reflects possibly transitory effects of supply chain disruptions and sharply rising shipping costs, which have also impacted exports from the region. But central banks will likely feel the need to address concerns about rising prices, perhaps following recent rate hikes in Korea, Turkey, and Russia. At a minimum, the likelihood that central banks will offer significant policy support in the current environment seems to have declined considerably.- Fiscal support may also be limited. While governments in the region were able to provide sizable fiscal stimulus in 2021, owing to relatively low public debt and limited debt held by foreigners, it is unlikely they will do so again. In fact, fiscal plans for many Asian countries have been based on the perceived need to rewind at least some of the increased spending from last year. While that may be revisited in some countries, another large stimulus across the region does not appear in the cards.

- Finally, the global environment appears considerably less supportive than was expected just several months back. Growth in the US and other advanced economies has slowed, again reflecting the impact of the Delta variant and disappointing vaccination take-up, even as inflation has increased well beyond earlier expectations. Fed Chairman Powell has repeatedly emphasized—including at the recent Jackson Hole meetings— that there are no plans to raise interest rates or even to begin tapering central bank asset purchases. But a few more bad readings on inflation could easily speed up the timeline for tightening. This combination of slower growth and higher rates in the advanced economies could make life very difficult for policy-makers in the region. A shift in expectations toward higher US rates would raise concerns about capital outflows and currency depreciation in the region, providing an additional argument for raising rates, at the same time that slower global growth lowers near-term prospects in the region.

None of this is to say that Asia will be plunged into recession or that it won’t continue to outperform other regions of the world. Nevertheless, the optimism of spring and summer now seems very much overdone, while the challenges to macroeconomic policy-makers have grown significantly more complex.