Japan has, for several decades, experienced a toxic combination of an aging and shrinking population, slow growth, and very large fiscal deficits and debt. Looking forward, Japan’s potential growth is expected to approach zero, in large part owing to its demographic profile (see IMF).

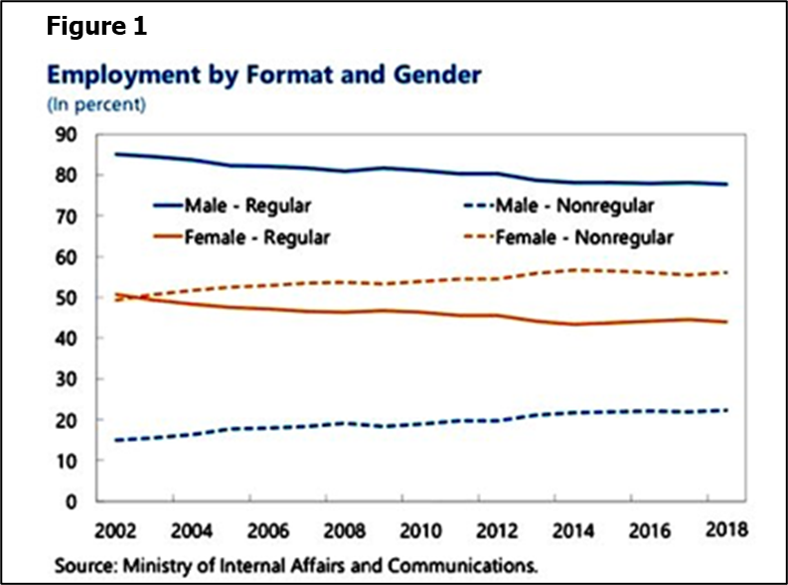

These interrelated issues have led policy-makers in Japan on a search for meaningful structural reforms to raise potential growth and offset the impact of eventual fiscal adjustment. One area that has received significant attention has been the Japanese  labor market, which is characterized by low female labor force participation; a significant duality between heavily-protected workers and “non-regular” workers with few protections and lower productivity; and limited flexibility regarding working conditions and modalities (Figure 1).

labor market, which is characterized by low female labor force participation; a significant duality between heavily-protected workers and “non-regular” workers with few protections and lower productivity; and limited flexibility regarding working conditions and modalities (Figure 1).

In this context, well before the start of the covid-19 crisis, the government was urging Japanese companies to increase their use of work from home, or telework, and has been offering subsidies to companies who take steps to do so. The thought has been that, by increasing flexibility in the work environment, women would be better able to participate and to work full-time. There are even an estimated one million Japanese adults who, for a variety of reasons, are unable or unwilling to leave their homes. Some of these so-called hikikomori ("pulling inward") might also be pulled outward, into the labor force. The well-known congestion of Japan’s urban mass transit might also be reduced.

Naturally, these efforts take on increasing importance in the current crisis environment. The hope has been that Japanese companies—like those elsewhere—could limit the economic harm of the virus by expanding their use of work from home. At the same time, such efforts could plausibly lead to longer-term changes in Japanese firms that would raise labor force participation and productivity, helping to support potential growth.

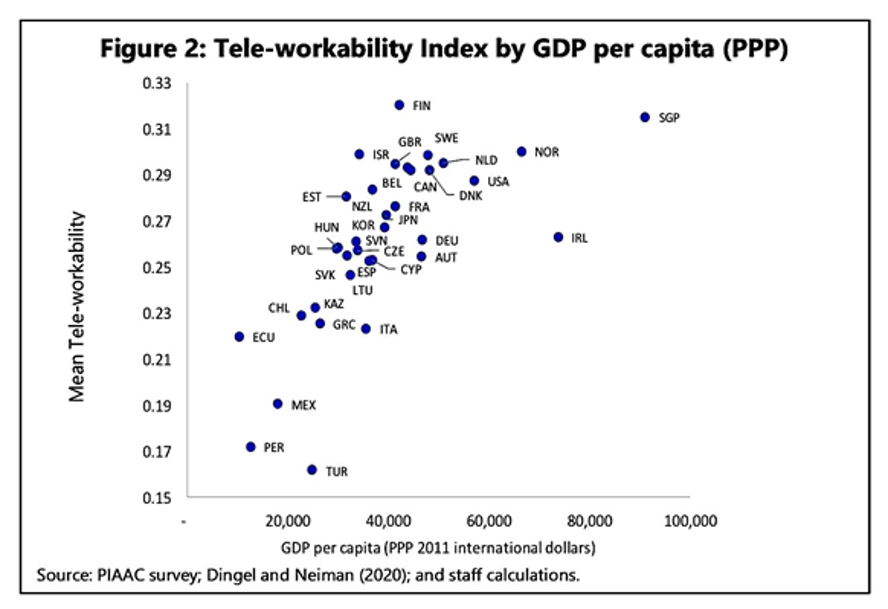

Such a development would, however, need to overcome a number of major obstacles. A 2020 paper by Brussevich, Dabla-Norris, and Khalid examines the potential of a range of countries to utilize work from home, based on the sectoral composition of their economic activity as well as indicators of access to technology. On this basis, Japan's “tele-workability index” appears to be somewhere in the middle rank (Figure 2). However, a number of country-specific factors suggest that such a rating may be optimistic:

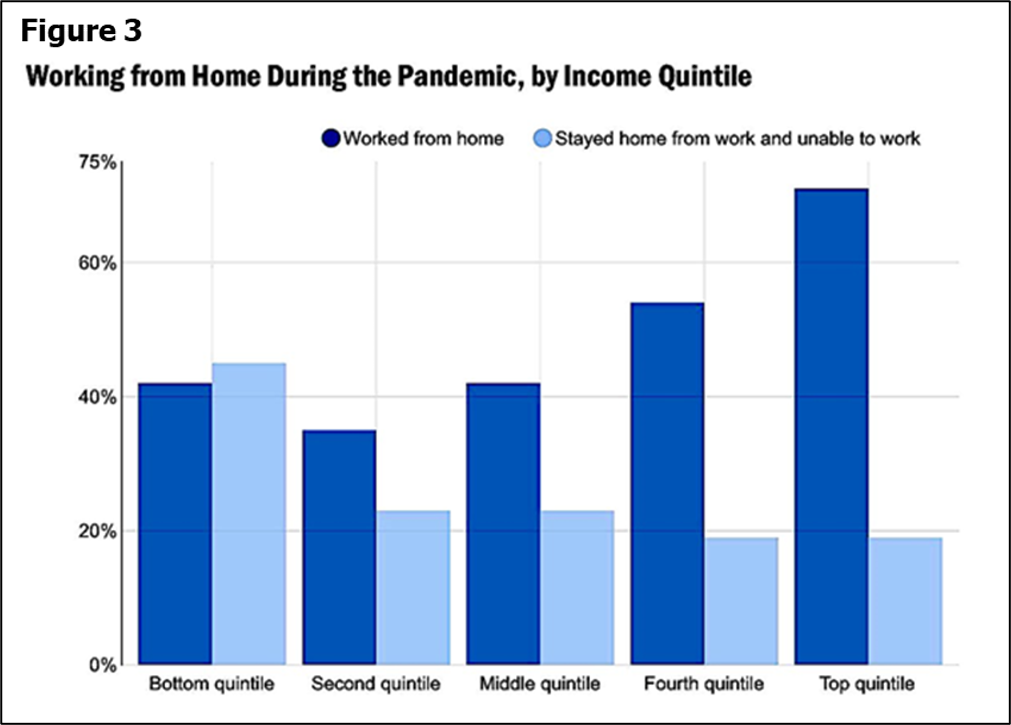

So, how has Japan done so far? There is not a lot of hard data on the first few months of the crisis. However, surveys and anecdotal information suggest that, while an effort is being made, Japan is finding it harder than many other advanced economies to work from home. The New York Times reported that a survey by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism in March found that fewer than 13  percent of workers nationwide were able to work from home. A similar survey conducted by Tokyo’s Chamber of Commerce in end-March found a somewhat higher 26 percent of companies had instituted telework. Data from the Brookings Institution suggests that the US, for example, has seen significantly more work from home (Figure 3).

percent of workers nationwide were able to work from home. A similar survey conducted by Tokyo’s Chamber of Commerce in end-March found a somewhat higher 26 percent of companies had instituted telework. Data from the Brookings Institution suggests that the US, for example, has seen significantly more work from home (Figure 3).

Efforts on the public policy side also give one some cause for pessimism. Legislation was introduced to the Diet to eliminate the need for a hanko for a range of documents. But even this seemingly simple change has faced opposition from some in the ruling party, and has not moved forward. And, as the New York Times reported, “companies applying for telework subsidies have reported needing to print out 100 or more pages of documents and deliver them in person.” Nevertheless, a market for digital alternatives to the hard copy system appears to be taking off.

But, we should perhaps not be too disappointed if progress has been on the slow side, given the existence of barriers that are both deeply embedded in society and not easily amenable to public policy. The covid-19 crisis will end, but Japan will continue to experience a shrinking labor force and tight job market. That may ensure that demands for increased workplace flexibility will eventually carry the day.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.